Dada was a revolutionary art movement that started in the early 20th century. It was developed as a reaction to the events of World War 1 and, due to its unique characteristics, spread to international borders.

The main ideas of Dadaism were that they rejected logic, aesthetics, reason, and capitalism. The artists were mostly against capitalism, as they believed it was the main cause of the war. And since they rejected the logic behind capitalism, their art reflected that “abandonment of logic” as can be seen by their absurd artwork.

The Dada art movement was absurd, nonsensical, and irrational and often made satirical, ironic, and humorous remarks. It was anti-war and anti-art.

However, we can’t fully credit Dada for pioneering the rejection of traditional artistic values. This art movement was itself inspired by the ideas of Cubism, Futurism, Constructivism, and Expressionism – all such movements that challenged traditional art and design practices.

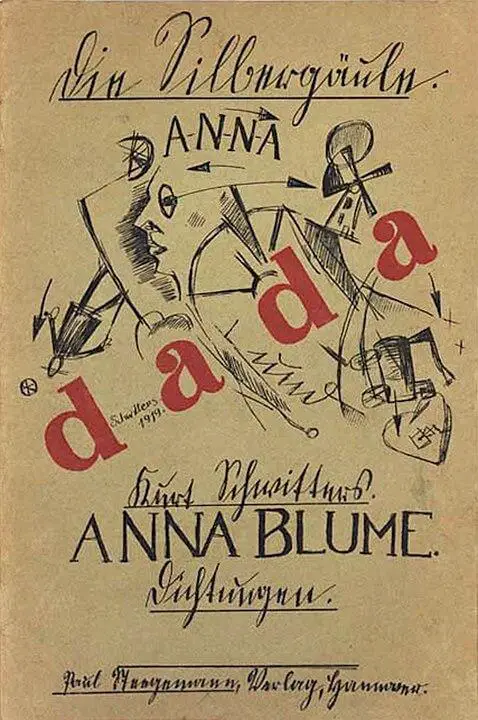

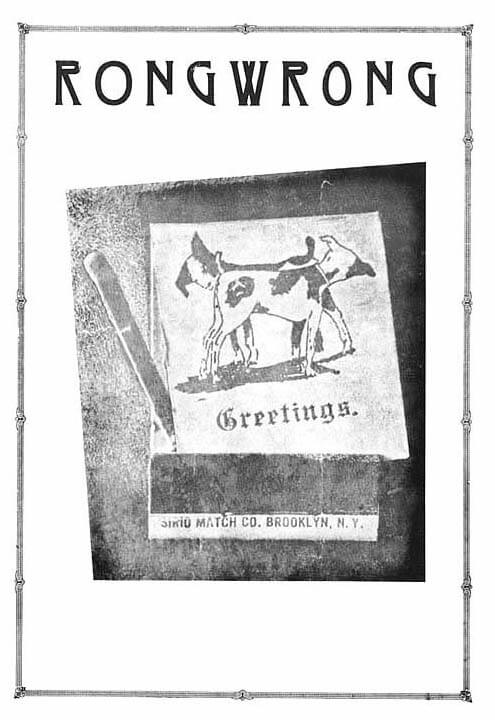

Dada went on to gain international influence in the form of poetry, literature, theater, art theory, art manifestos, graphic design, and visual arts.

In this article, we’ll discuss the origins of Dada, its characteristics, popular Dada artists, and the lasting impact it had on graphic design

Origins of Dadaism

Dadaism was influenced by the values, beliefs, and principles of prior art movements. These include Futurism, Cubism, Expressionism, and Constructivism.

The exact origin of the Dada art movement is unknown, however, most historians believe that Dada originated in Zürich, Switzerland.

Certain phases led to the development of Dadaism the way we know it today. So, we’ll break these down one by one.

Zürich, Switzerland

As WW1 broke out, Zürich seemed like the ideal place to form a center discussing the ideas of a new form of art. In Zürich, writer Hugo Ball with his girlfriend Emmy Hennings, founded the Cabaret Voltaire in 1916.

The Cabaret Voltaire was a nightclub. Its name was derived from the French philosopher Voltaire, who used to mock religious and philosophical beliefs through his novels. The name seemed fitting to represent the center of a movement that was also built upon mocking traditional values and making fun of conservative beliefs.

After the establishment of the Nightclub, the Cabaret Voltaire became a hangout for Dada artists to showcase art to express their disgust with the World War and discuss the matters that started it (capitalism.)

“Our cabaret ‘Cabaret Voltaire’ is a gesture. Every word that is spoken and sung here says at least this one thing: that this humiliating age has not succeeded in winning our respect.”

Hugo Ball

Since Switzerland had a neutral political status, it allowed Dadaists to create work that expressed their social, political, and cultural ideas. They did this by using shock art, deliberate irony and offense, and excessive variety.

Berlin, Germany

Dada in Berlin started when artist and writer Raoul Hausmann published his manifesto “Synthetic Cino of Painting” in 1918. In it, he attacked and criticized Expressionism and stated the need for newer techniques of creating art.

“A child’s discarded doll or a brightly colored rag are more necessary expressions than those of some ass who seeks to immortalize himself in oils in finite parlors.”

Raoul Hausmann

Dadaism in Germany was different from Zürich, it didn’t emphasize its anti-art philosophy. Instead, the works of the Dadaists in Berlin seemed to be more political, through the publication of manifestos and propaganda.

Since Germany was the center of attention in the First World War, seeing the war-torn activities had an impact on the Dada artists.

Dada seemed to see its greatest uplift in Berlin, as some of the popular art techniques like Collages and Photomontage, were invented. There were also a few manifestos published that distinguished Dada art from traditional art.

After the war, around 1920, many of its members published political magazines, arranged exhibitions, and even established their own party called the Central Council of Dada for the World Revolution.

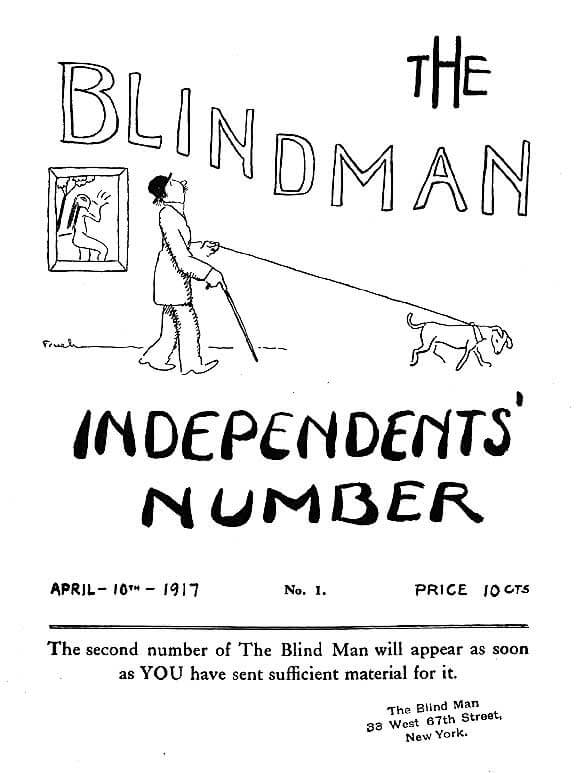

New York, USA

In the USA, many artists shared a similar philosophy as the Dadaists in Zürich although they didn’t associate themselves with the movement. Hans Richter echoed this by saying that the Dada movement in the USA, was happening “quite independently”. They did, however, start calling their activities Dada later.

Dada started to take root in New York when Dadaists Marcel Duchamp and Frances Picabia traveled to the USA from France and met with the American artist Man Ray. Together they criticized traditional artistic values and principles and became the driving force calling for radical anti-art in America.

American Dada was different from European Dada. In Europe, the artists focused more on absurdity, whereas in America they made use of irony and humor.

It was also during this time that Duchamp introduced his idea of “Readymades” – everyday objects that were re-imagined as pieces of art. In 1917 he created his most iconic piece, Fountain, a displaced urinal displayed as a fountain signed “R.Mutt”.

After gaining recognition in New York, most of the renowned artists moved to Paris, France.

End of the Dada Movement

The movement lacked any real order or hierarchy from the start. Several disagreements between the members themselves, combined with the misunderstandings of the movement led to Dada’s short-lived downfall – ending in 1922.

Despite the end of this movement, many notable Dada artists went on to create groundbreaking artworks and had a profound impact on other influential design movements that followed

Characteristics of Dada Art

Dada Art often had absurd and unconventional techniques and characteristics. These art forms arose due to the artists embracing chaos and irrationality in their artworks.

Their art also rejected the reasons/logic behind the capitalist society which they stated was the main reason for the war. They thought, “If the war doesn’t make sense, why should our Art?”

Despite there not being an exact definition of what entails “Dada Art” we can analyze the art pieces produced during that era and get a sense of the characteristics shared by the artists’ works.

Collage

The Dadaists were inspired by Cubism and imitated the way of cutting and pasting pieces of material together to form complete images. Dada incorporated the cutting and pasting together of found material – this included tickets, stamps, posters, stickers, etc.

In 1917, Jean Arp, also known as Hans Arp, invented the “chance collage” technique. This was a technique where a collage was produced by taking a few squares and randomly dropping them on an empty canvas. The artist would then paste/stitch together the pieces in the place they would land – giving it a random order.

Cut-Up Technique

The cut-up technique refers to expanding the collage techniques to written words. Tristan Tzara had stated its technique:

TO MAKE A DADAIST POEM:

- Take a newspaper.

- Take some scissors.

- Choose from this paper an article of the length you want to make your poem.

- Cut out the article.

- Next, carefully cut out each of the words that make up this article and put them all in a bag.

- Shake gently.

- Next, take out each cutting one after the other.

- Copy conscientiously in the order in which they left the bag.

- The poem will resemble you.

And there you are – an infinitely original author of charming sensibility, even though unappreciated by the vulgar herd

Tristan Tzara

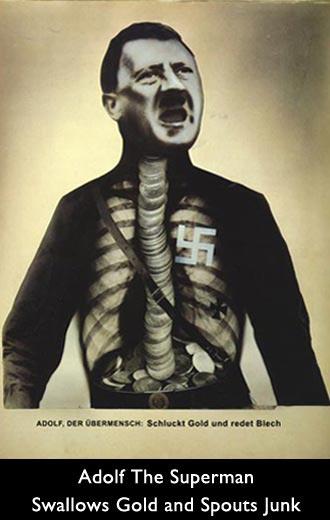

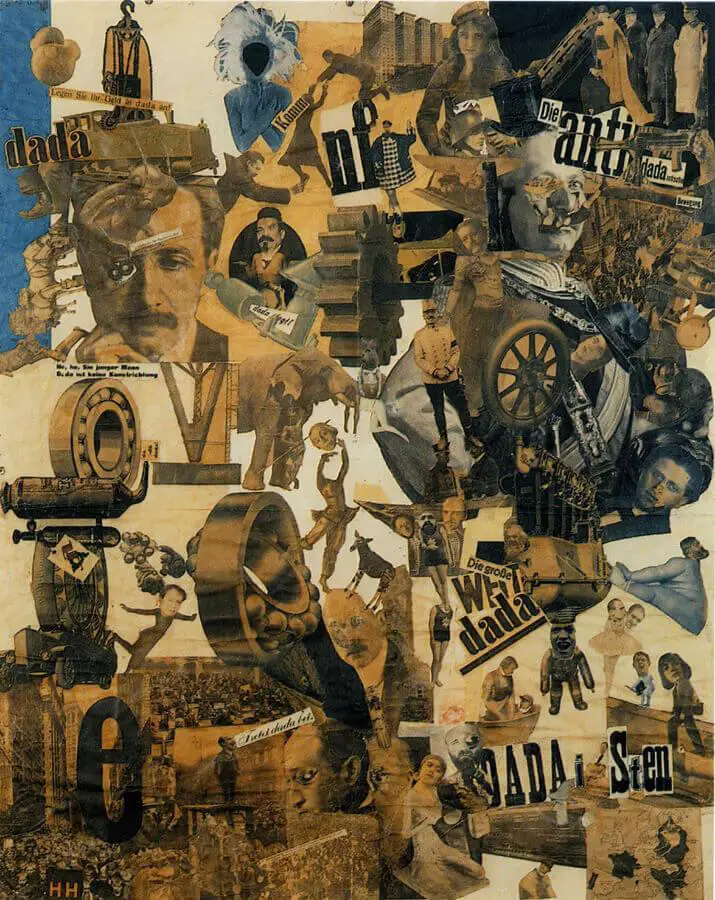

Photomontage

The photomontage is the technique of cutting and pasting together different images from press releases and other forms of media. This technique was collectively developed by George Grosz, Hannah Höch, John Heartfield, and Raoul Hausmann during the Berlin Dada.

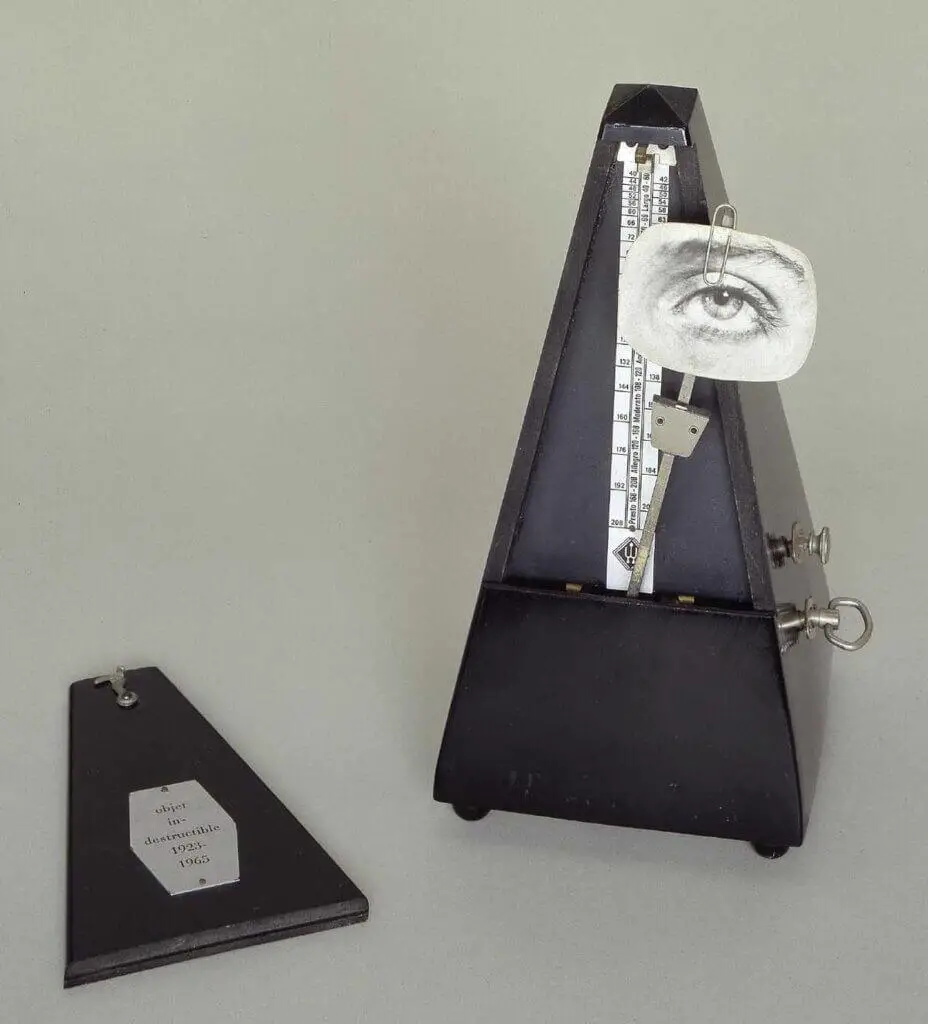

Assemblage

Assemblages were 3D collages assembled with everyday objects. The artist takes various objects and fixes them together with glue, nails, and any other bonding agent to make a sort of 3D work of art.

Readymades

Readymade was a term coined by Dada Artist Marcel Duchamp. It referred to works of art made by manufactured objects. He states in the book, The Art of Assemblage, that it’s “…based on a reaction of visual indifference, with at the same time a total absence of good or bad taste…”

Famous Dada Artists

Hugo Ball (1886-1927)

Hugo Ball is best known for his role as one of the founders of the Dada movement and for his avant-garde poem titled “Karawane,” which was recited as part of his performance at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich.

He played a crucial role in the establishment of the Dada movement in Zürich, Switzerland, during World War I. His performances at the Cabaret Voltaire set the tone for Dadaist anti-art, characterized by absurdity and a rejection of traditional norms.

Tristan Tzara (1896-1963)

Tzara is known for his manifesto titled “Dada Manifesto” (1918), which set the principles of the Dada movement, advocating for chaos, lack of order, and rebellion against tradition.

As one of the intellectual leaders of Dada, Tristan Tzara’s manifesto helped define the movement’s philosophy and its rejection of established artistic practices. He was a prominent figure in spreading Dada ideas beyond Zürich to Berlin, Germany. His rigorous campaigns to spread Dadaist ideas influenced the formation of Dadaist groups worldwide.

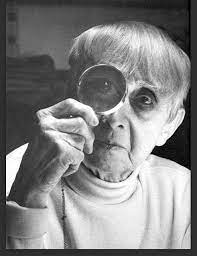

Hannah Höch (1889-1978)

Hannah Höch is celebrated for her photomontage works, with “Cut with the Dada Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany” (1919-1920) being one of her most famous pieces.

Höch’s photomontages challenged traditional gender roles and societal norms. She was the first female Dada Artist and her art was both a reflection of and a critique of the chaotic post-World War I era in Germany. The themes of her artwork often had a touch of feminism as well, typically calling out and making known the ill ways in which women were treated.

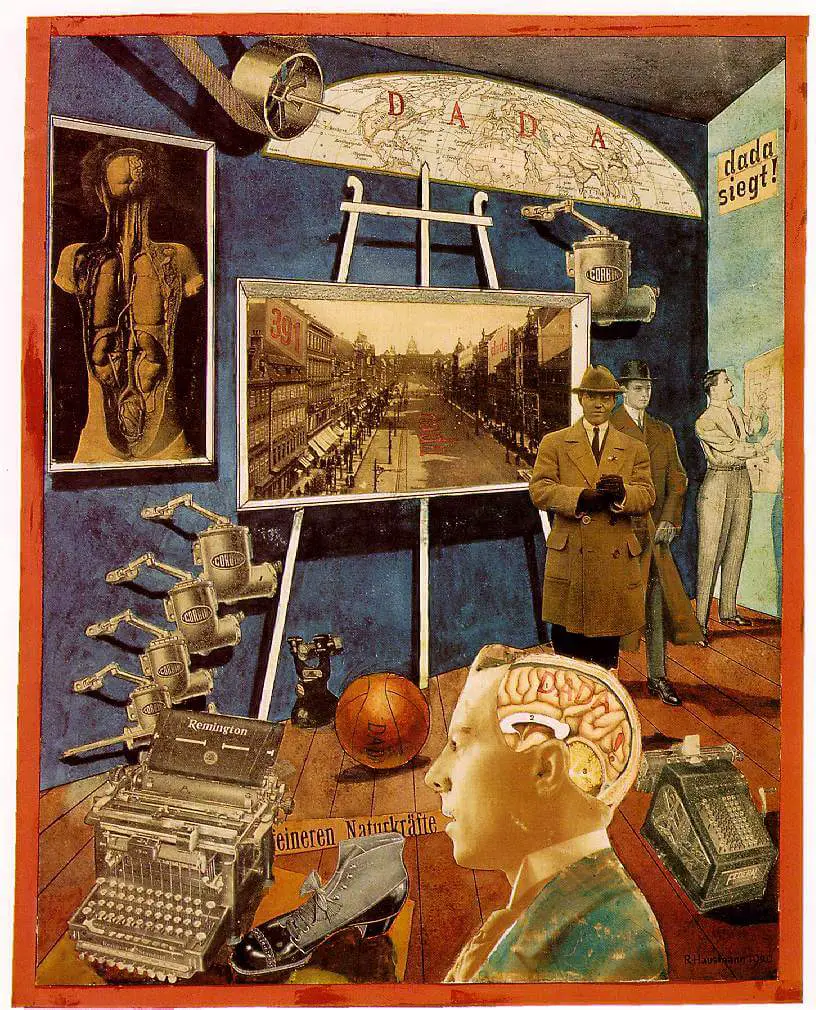

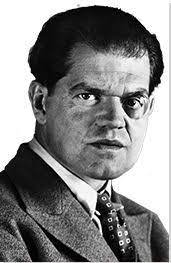

Raoul Hausmann (1886-1971)

Raoul Hausmann is known for his assemblage sculpture titled “Mechanical Head (The Spirit of Our Time)” (1919), which incorporated found objects to create a disorienting and thought-provoking piece.

Hausmann was a key figure in Berlin, and his innovative use of found materials in art challenged traditional notions of artistic creation. His works exemplify Dada’s embrace of the absurd and rejection of established aesthetics.

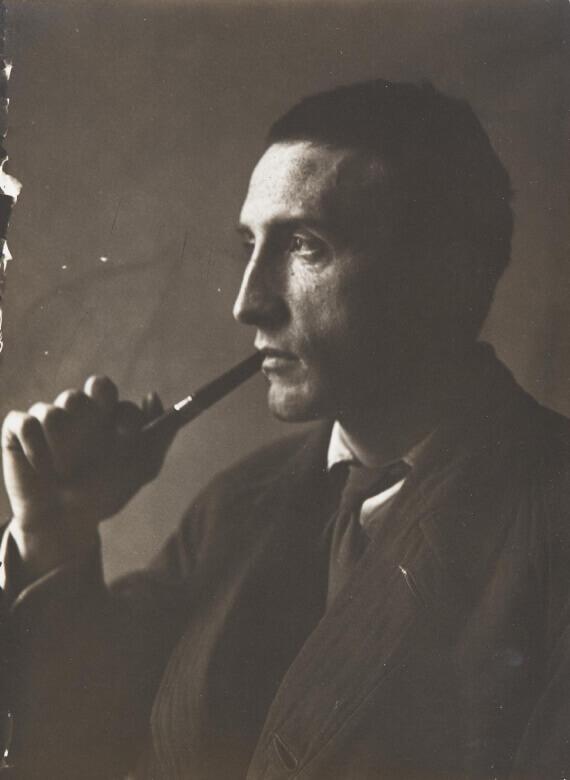

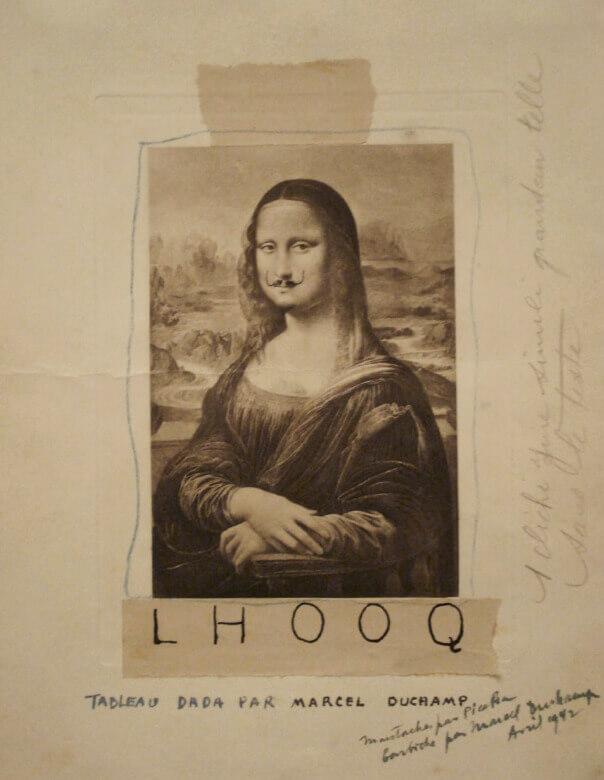

Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968)

Duchamp’s “Fountain” (1917), a urinal-turned artwork, is one of the most iconic pieces of the Dada movement. He is also known for “L.H.O.O.Q.” (1919), a Mona Lisa painting with a mustache.

Marcel Duchamp is arguably the most influential Dada artist, pioneering the concept of “readymades,” ordinary objects repurposed as art. His works challenged the very definition of art and had a lasting impact on conceptual art and the avant-garde.

Together, these Dada artists pushed the boundaries of artistic expression, calling for absurdity, anti-art, and a rejection of conventional values.

Their work not only challenged the art world but also had a profound impact on the broader cultural and intellectual landscape of the 20th century, leaving a lasting legacy that continues to influence contemporary art movements.

Legacy of Dada

Dadaism with its rejection of logic and welcome to chaos and absurdity, paved the way for future art and design movements. Although Dada formed an anti-art movement that disregarded aesthetics, it still managed to create a style of its own.

Not only that but even when trying to move away from any sort of logic or rationale, Dada found itself being discussed as a subject in many art and graphic design books. It’s given an equal standing of importance as other design movements that evolved art and design to what we know today.

Apart from its philosophy, Dada also made significant contributions to the social and political status of art.

Finally, despite Dada’s ultimate end in 1922, it went on to influence other design movements such as Surrealism, Pop Art, and Postmodernism.