Futurism was an art and social movement founded in the early 20th century by the Italian poet, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. It went on to have a great influence over multiple disciplines including graphic design, architecture, music, product design, interior design, literature, and many more.

The main characteristics of futurism included an emphasis on modernity, violence, technology, and speed. It was built upon a strong rejection of the past and its heritage while encouraging originality.

Although it originated in Italy, it went on to influence other countries such as Russia, where a group of artists and poets created their group based on the principles of Italian Futurism, and started the Russian Futurism movement.

This movement is important to learn about as it went on to influence other major art movements such as Art Deco, Constructivism, and Dada – which went on to influence graphic design.

In this article, we’ll learn more about Futurism, its history, its importance, and some of the major futurists that provided fuel to the movement. We’ll also glance at some examples of futurist art and design as well as some of the major works produced during that era.

History of Futurism Design

The movement came about when Filippo Tommaso Marinetti published the Futurist Manifesto in a French newspaper titled Le Figaro in 1909.

Within the manifesto, Marinetti had added an emphasis on aggression, war, violence, modernity, and a rejection of past ideas and principles. The following extracts from the manifesto prove exactly that:

“We want to glorify war – the only hygiene for the world – militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of the anarchists, the beautiful ideas which kill, and contempt for women.”

and

“We want to demolish museums and libraries, fight morality, feminism, and all opportunist and utilitarian cowardice.”

Marinetti’s philosophy was to reject the culture of the past and create original ideas. Originality was so pinnacle to the Italian poet that even if war and violence were necessary to attain it, he stood to support it.

He even suggested that man-made objects should replace nature and dominate it through the use of technology.

This may explain why he was attracted to industrial inventions such as the car, the plane, and machinery.

The Manifesto of the Futurist Painters (1910)

Later joining Marinetti in his pursuit were Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Giacomo Balla, Gino Severini, and Luigi Russolo.

Together, they signed another document known as the Manifesto of the Futurist Painters in 1910 that stated:

“We will fight with all our might the fanatical, senseless, and snobbish religion of the past, a religion encouraged by the vicious existence of museums. We rebel against that spineless worship of old canvases, old statues, and old bric-a-brac, against everything which is filthy and worm-ridden and corroded by time. We consider the habitual contempt for everything which is young, new, and burning with life to be unjust and even criminal.”

This manifesto was then followed by another follower of the Futurist movement, this time composed by the female French writer, Valentine de Saint-Point.

The Manifesto of Futurist Women (1912)

In response to the statements mentioned in the Futurist Manifesto against women, Valentine de Saint-Point proposed The Manifesto of Futurist Women stating that:

“It is absurd to divide humanity into men and women. It is composed only of femininity and masculinity. Every Superman, every hero, no matter how epic, how much of a genius, or how powerful, is the prodigious expression of a race and an epoch only because he is composed at once of feminine and masculine elements, of femininity and masculinity: that is, a complete being…

It is the same way with any collectivity and any moment in humanity, just as it is with individuals. The fecund periods, when the most heroes and geniuses come forth from the terrain of culture in all its ebullience, are rich in masculinity and femininity.

Those periods that had only wars, with few representative heroes because the epic breath flattened them out, were exclusively virile periods; those that denied the heroic instinct and, turning toward the past, annihilated themselves in dreams of peace, were periods in which femininity was dominant. We are living at the end of one of these periods. What is most lacking in women as in men is virility.

That is why Futurism, even with all its exaggerations, is right.”

Despite the arguments made by Valentine, she had agreed with the core values of Futurism mainly due to its focus on virility. F.T. Marinetti later claimed Valentine as the “first futurist woman.”

Later on, many other women started to join the movement including Marinetti’s own wife, Benedetta Cappa Marinetti. She, later on, became one of the first painters to paint in Aeropittura or Aeropainting.

Why is Futurism Important in Graphic Design?

If you’re a student of graphic design or even an intermediate exploring the history of it, you may ask yourself the importance of learning about Futurism.

Learning about this design movement is important as it went on to influence many other major art movements that morphed graphic design into what it is today. Futurism itself also had quite a lot of impact on the visual aesthetic of graphic design.

Let’s explore some examples of Futurism. This will give you a better idea of how the art movement slowly started to take shape.

Futurism Graphic Design Examples

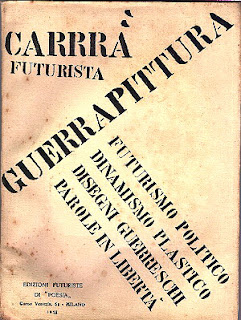

Futurism Typography

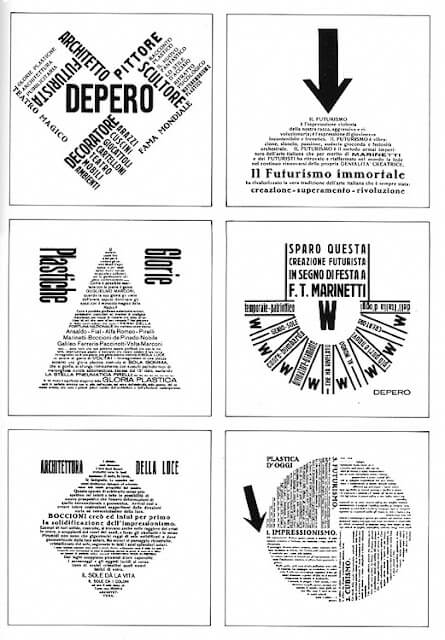

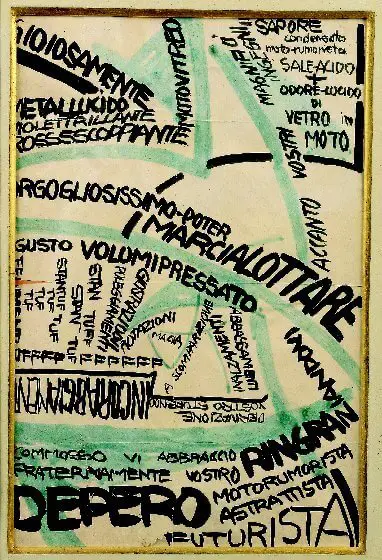

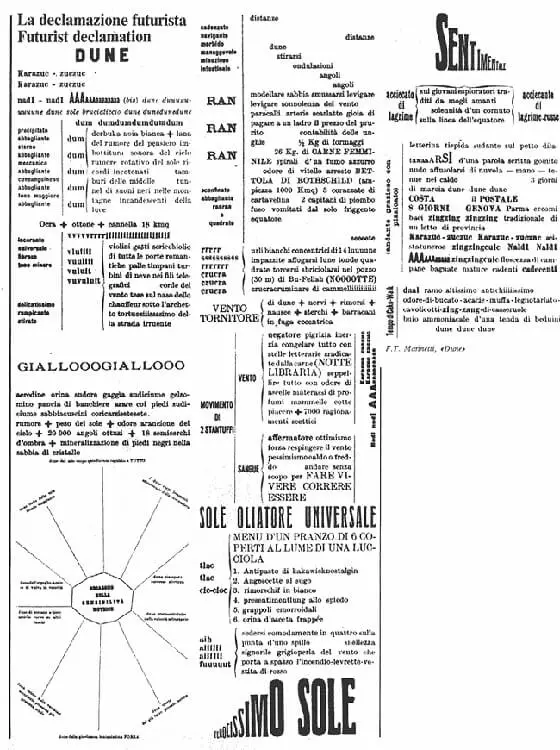

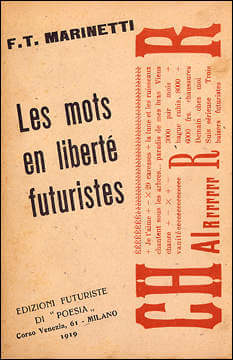

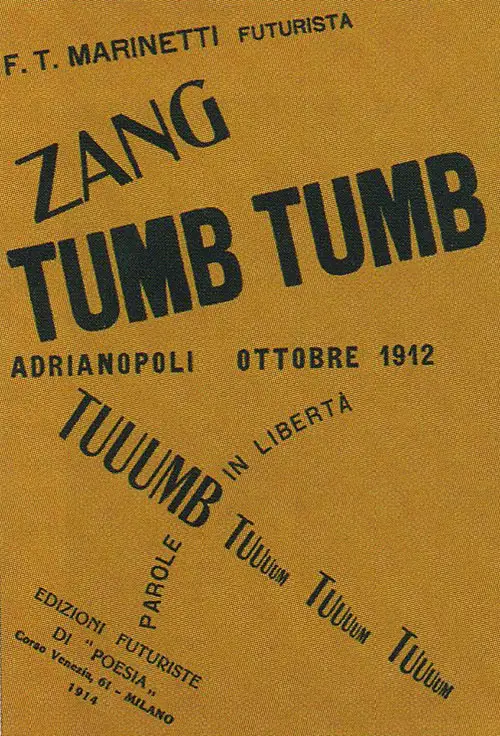

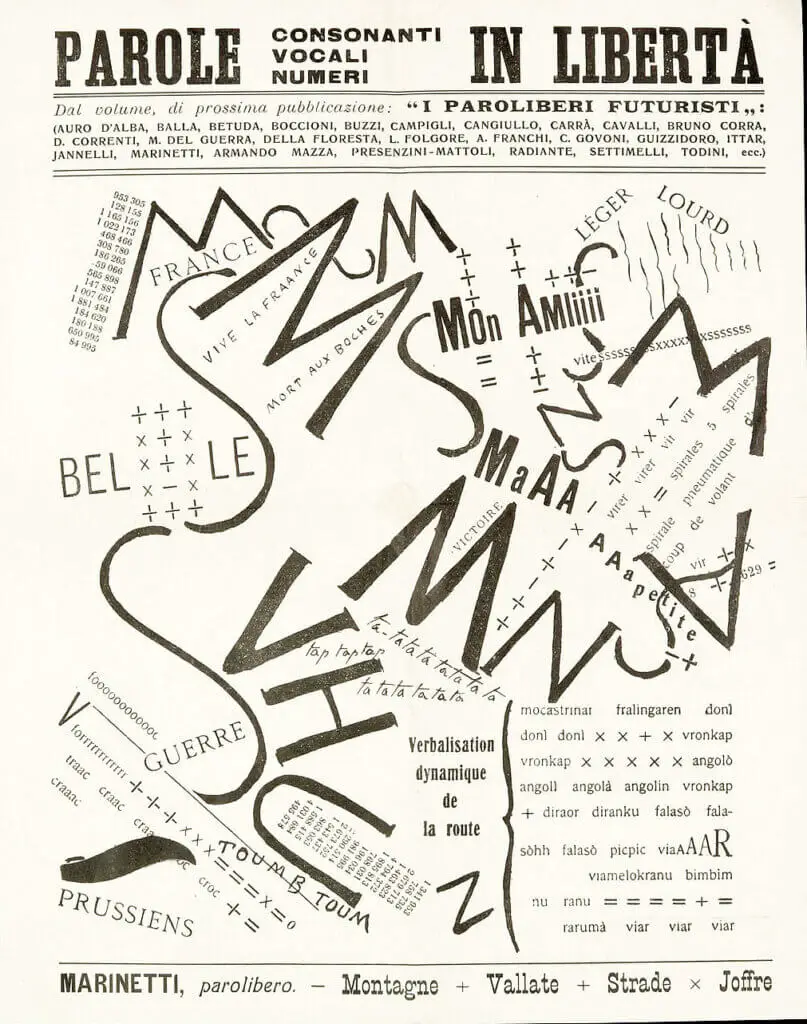

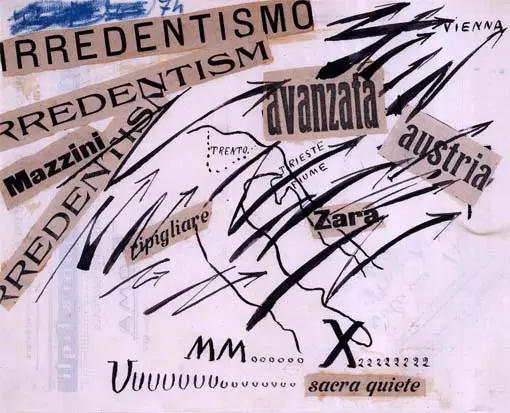

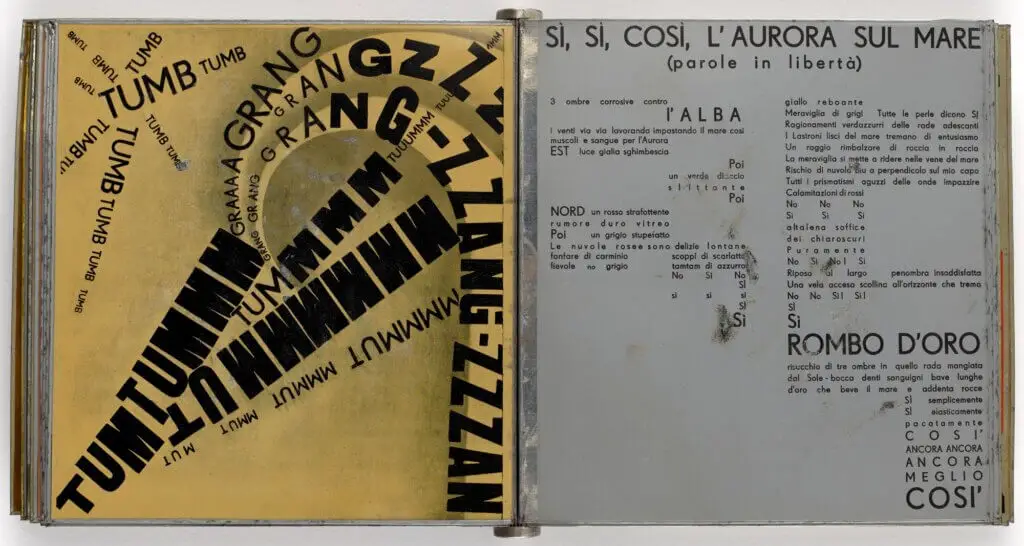

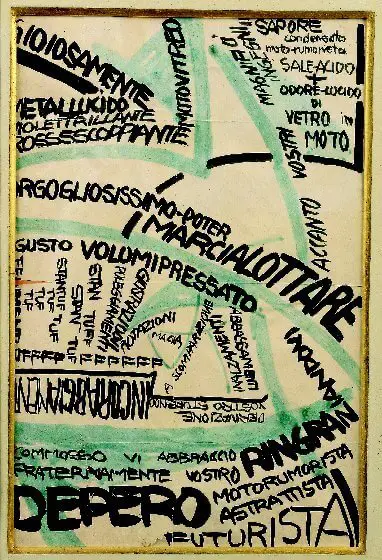

Ever since the invention of the Gutenberg press, graphic designers were used to following the rules of typography – aligning their text horizontally or vertically across a page. For Martinetti though, these rules acted as constraints, which led to him disregarding the uniformity that had existed throughout the visual arts.

Regarding the rejection of harmonious designs, he said:

“The book will be the futurist’s expression of our futurist consciousness. I am against what is known as the harmony of a setting. When necessary, we shall use three or four columns on a page and twenty different typefaces. We shall represent hasty perceptions in italics and express a scream in bold types… a new painterly, typographic representation will be born out of the printed pages.”

In another manifesto, he says about typography:

“I have initiated a typographical revolution directed against the bestial, nauseating sort of book that contains passéist poetry or verse à la D’Annunzio12—handmade paper that imitates models of the seventeenth century, festooned with helmets, Minervas, Apollos, decorative capitals in red ink with loops and squiggles, vegetables, mythological ribbons from missals, epigraphs, and Roman numerals. The book must be the Futurist expression of Futurist thought […]. My revolution is directed against the so-called typographical harmony of the page.”

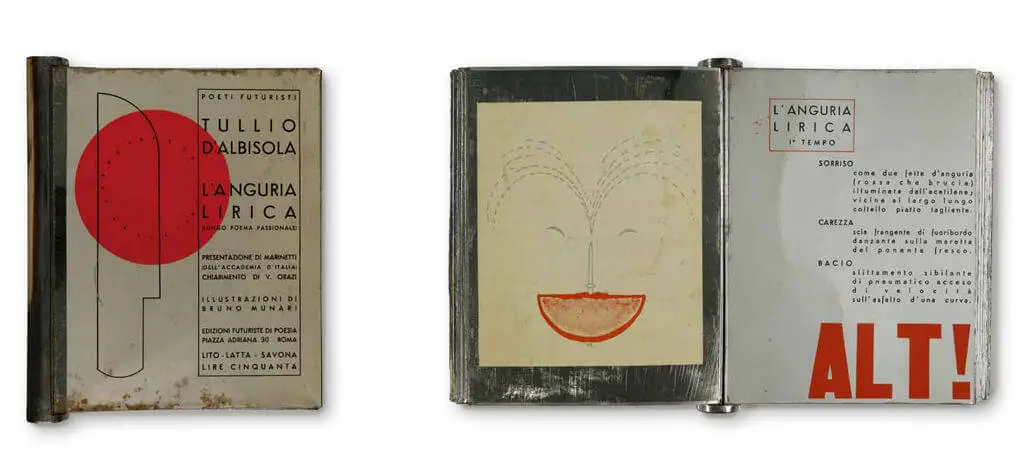

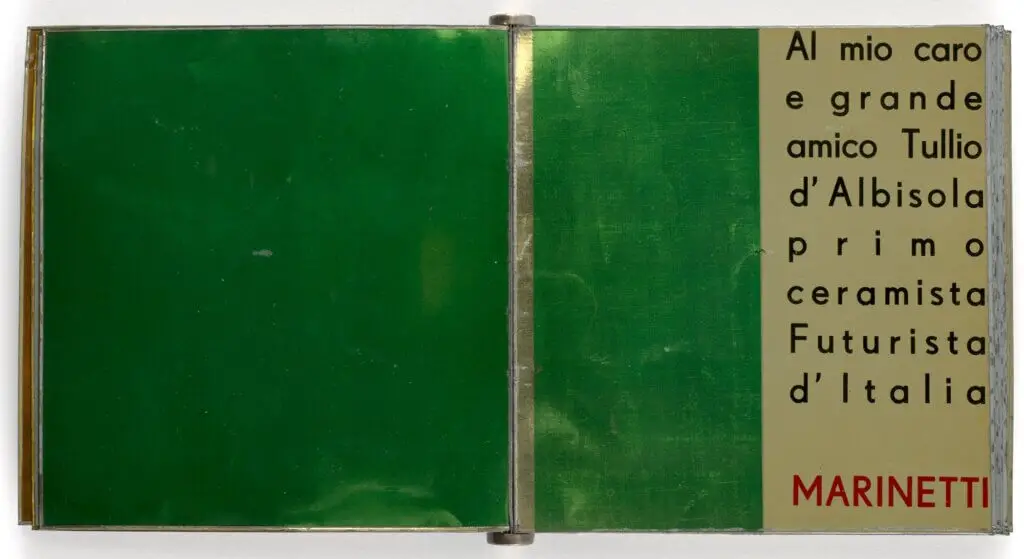

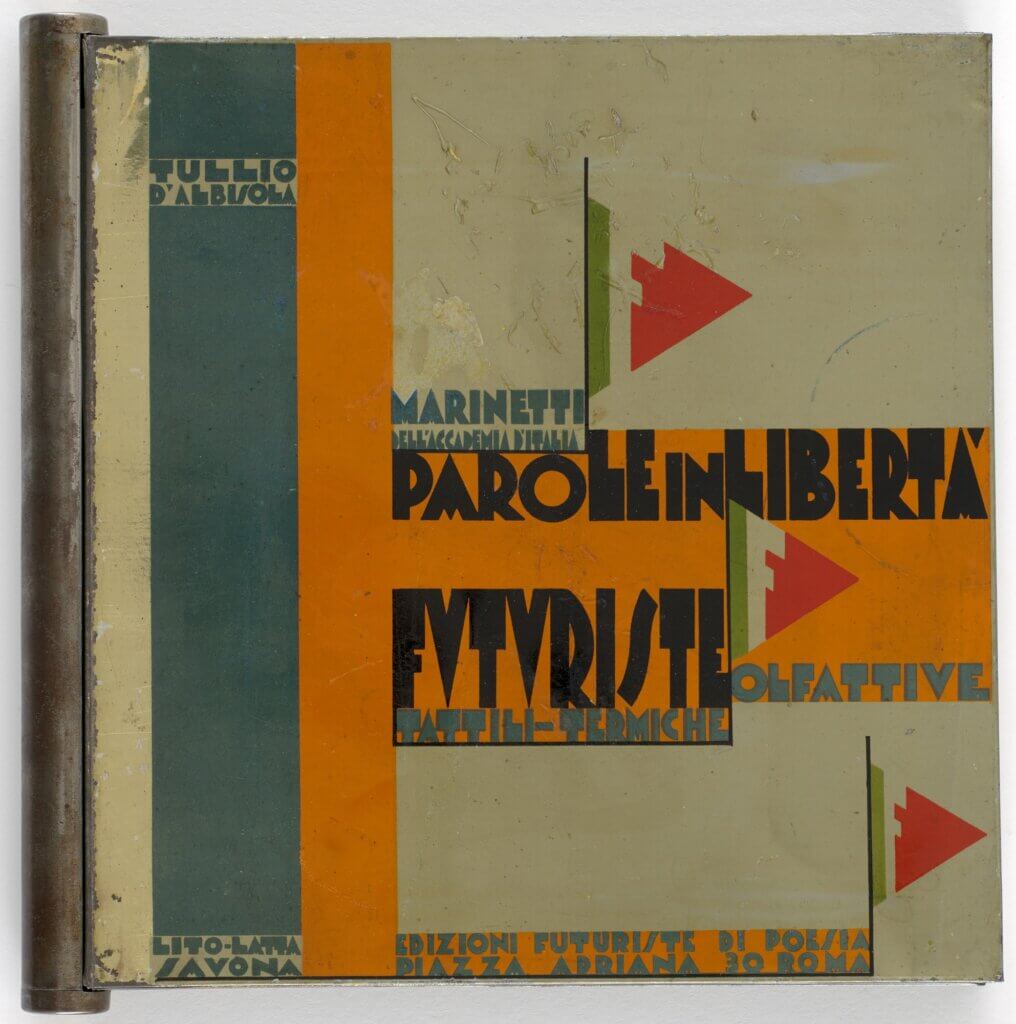

Not only did Futurism challenge the harmony of the text on the page, but it extended to even changing the form, binding, and material of printed books.

This philosophy however gave birth to many interesting examples of innovative typography in the Futurism design movement.

Futurism Poster and Cover Design

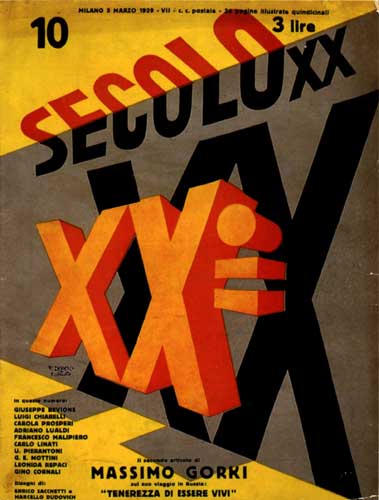

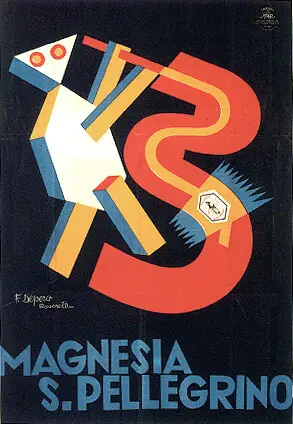

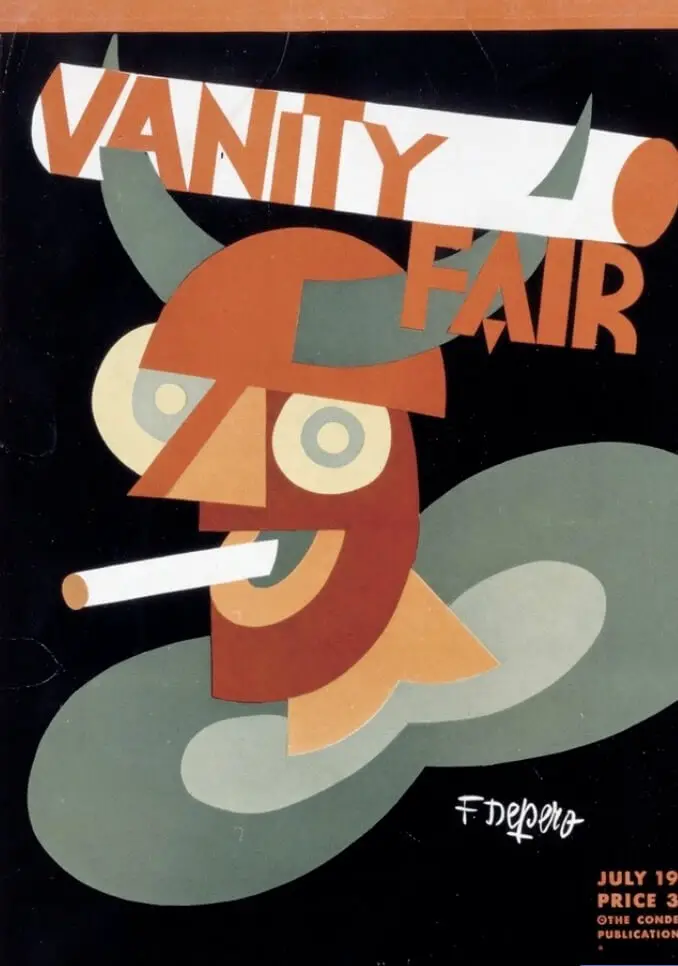

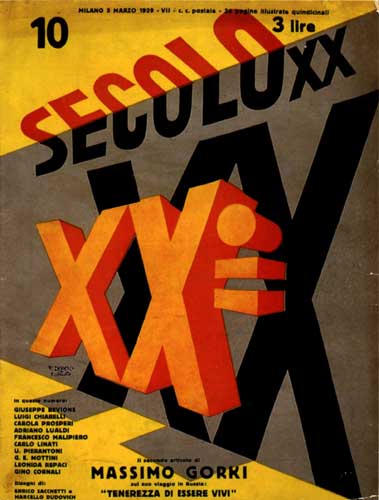

Many unique print designs also came forward with the rise of Futurism. Fortunato Depero in particular worked with a few magazines and was considered to design their covers for them. He even worked for Vanity Fair and Vogue and designed covers for them as well.

Futurism Book Design

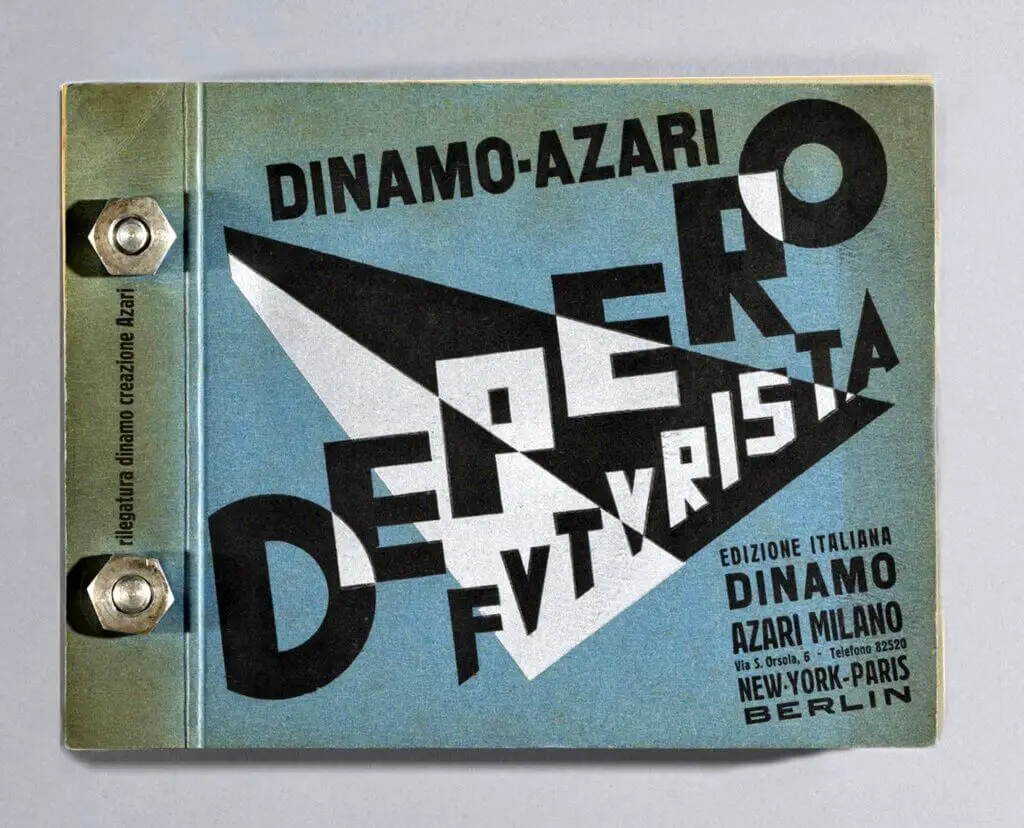

As mentioned before, the futurists were determined to change any old form of art. So, what started with innovative typography in an attempt to break away from the constraints of traditional typography, Futurism progressed to changing the entire form of the book.

This can be most vividly seen with the introduction of Fortunato Depero’s first experimental work: Depero Futurista. Also known as the bolted book for its unique design, this book proved to be one of the first successful book objects proposed by futurists.

Then followed other innovative book designs.

You might have noticed the unique spine of the book. Its binding was made from steel as an attempt to challenge the traditional way of biding a book together.

Characteristics of Futurism Design

There’s no doubt that Futurism had a great impact on art and design in the early 20th century. However, you may ask yourself what it is about a certain piece that makes it Futurism.

There are certain characteristics of futurist design, which we discuss below:

- Divisionism – many futurists took inspiration from divisionism, the process of breaking down color and light forms into a series of dots and patches that interact together

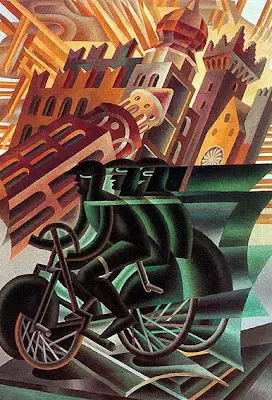

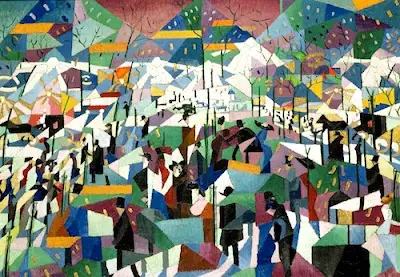

- Dynamism – the visual representation of speed and movement. It was used in most notable artworks in the futurist era as a way to depict motion in static images.

- Modernity – the futurists were obsessed with anything new in an attempt to detach themselves from their cultural past

- Multilinear lyricism – a technique of using expressive typography by varying the columns, shapes, and sizes of the text according to the theme or impact the designer wants to create

Notable People of the Futurism Movement

As mentioned earlier, F.T. Marinetti was joined by many influential painters, artists, and architects within Italy to further develop his movement. Their contributions towards the movement gave Futurism the leverage it needed to have an impact on the art world.

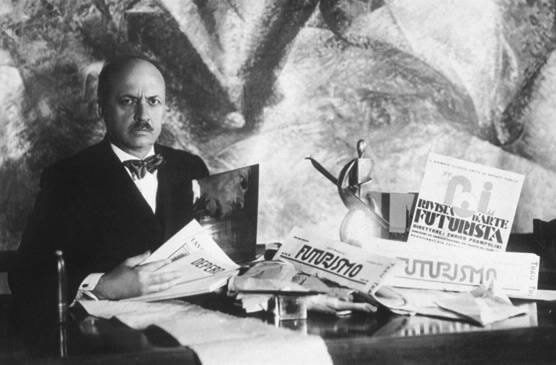

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti was an Italian poet and the founder of the Futurism movement. He was the first to propose the idea of rejecting Italian history, culture, and heritage to make way for a modern revolution driven by speed, youth, war, technology, and violence.

It is believed that F.T. Marinetti got the idea of the Italian Futurism movement in 1908 when he was driving along the road in Milan. He was out and about in his car when he had to make a sharp turn due to some cyclists along the path – leading Marinetti to crash his car.

This incident, through the lens of the Italian poet, was seen as a standoff between old and new machinery. He was so intrigued by the idea of newer, innovative machinery such as the plane, the car, the train, etc. that he called for the destruction of all old traditions to welcome new ones.

Aside from his contributions to the history of visual arts, he also held strong political beliefs. He merged his Futurist party with the Italian Fascist Party in 1919 and co-wrote the original Italian Fascism manifesto. During the Fascist regime, Marinetti hoped to make Futurism the dominant style of art and way of life in Italy, but failed partly due to wide condemnation of Fascism and the labeling of modern art as “degenerate art.”

After volunteering in WW2, he later died of cardiac arrest on 2nd December 1944.

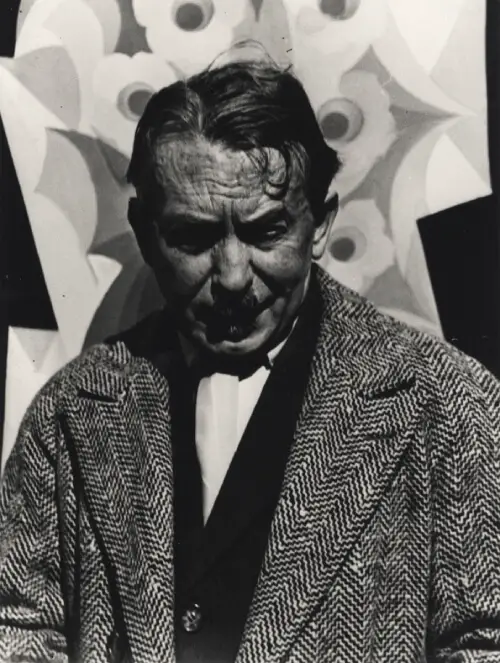

Fortunato Depero

Fortunato Depero was one of the most influential personalities to have joined the Futurism cause. He was born in Fondo, Italy, and was schooled in the Scuola Reale Elisabettina in Rovereto where he specialized in applied arts.

In 1910, he worked as an apprentice to a marble worker to further his expertise in the applied arts. It was in 1913 when Depero discovered Marinetti’s article on Futurism from the published paper, Lacerba. This led to him dedicating his first piece to the movement, Spezzature–Impressioni: Segni e ritmi which was a collection of his poetry and illustrations.

Shortly after, he had the privilege to meet Marinetti in person at the Galleria Permanente Futurista in Rome. There Marinetti introduced him to other futurists. In 1915, Depero along with Giacoma Balla wrote the Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe manifesto which called for bringing together all forms of media in art to give a “new life to the world.”

During the second wave of Futurism, known as il secondo Futurismo or the “Second Futurism”, Depero made huge leaps in his art style by reviving Futurist typography and bringing forth an innovative typographic expression.

Giacomo Balla

Giacomo Balla was an Italian painter, art teacher, and poet. He enrolled in the Accademia Albertina and studied light forms of the works of Seurat and Signac. Marinetti’s proposed idea of Futurism attracted Balla ever since he came across its original manifesto in 1909 published in the newspaper Le Figaro.

Inspired by the movement, Balla had distanced himself from realistic painting techniques and had instead started to adopt the Futurist style. By 1913-1914 his paintings started to reflect the characteristics of Futurism with the main focus being on the depiction of speed.

Around the end of the 1920s, Balla started to distance himself from the Futurism movement.

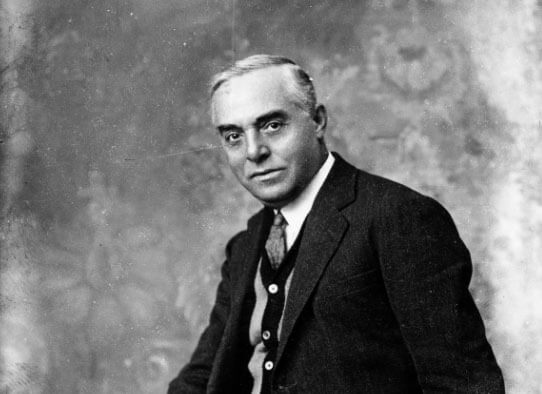

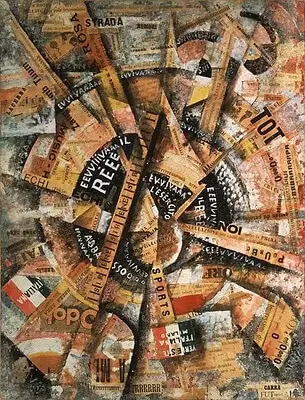

Carlo Carrà

Carlo Carrà was good friends with Boccioni and Russolo and had met Marinetti in a cafe at Port Vittoria. Over there, Carra alongside the other Futurist artists had written a manifesto to inspire young artists to break free from conventional approaches to art and adopt the Futurist style – the style of the future. In his own words, he says:

“Marinetti greeted us warmly. After a long analysis of the state of art here at home, we decided to publish a manifesto for young Italian artists urging them to shake themselves free of the stupor that was suffocating all higher aspirations.”

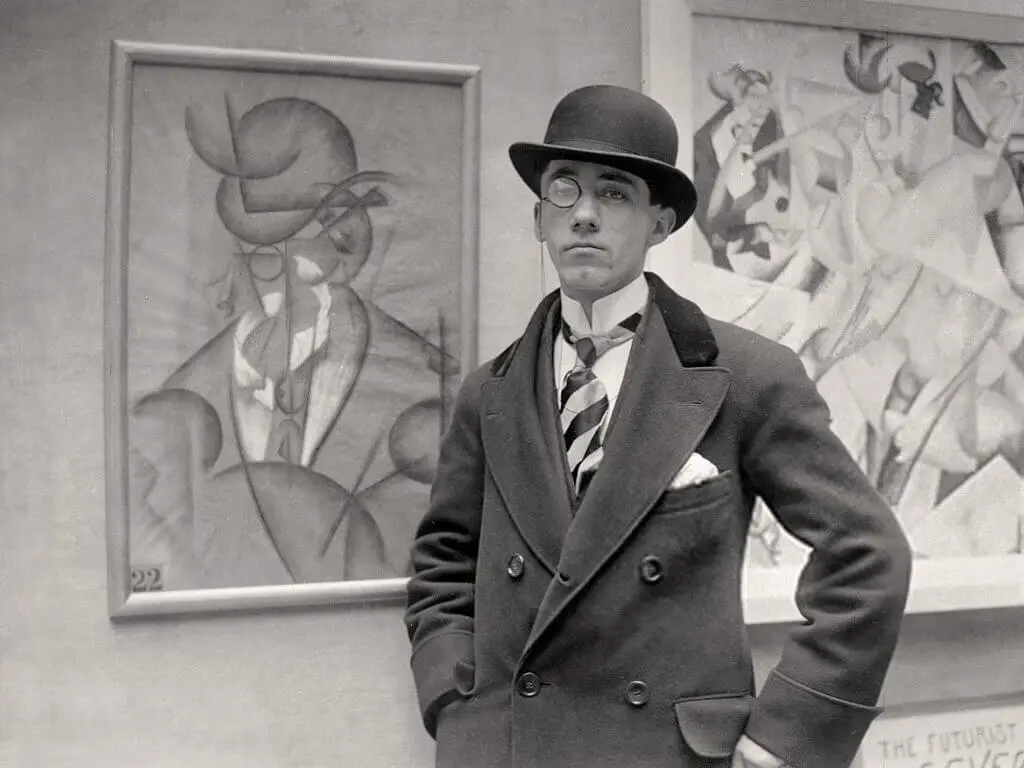

Carra had also participated in the 1912 futurist exhibition at the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, presenting some of his greatest works.

However, after the first world war, he openly rejected the idea of Futurism’s dynamism and instead proposed a return to the simplicity and correctness of the arts. He later left Futurism and joined Giorgio de Chirico, an influential artist, and writer, to develop a new art movement known as “Metafisica.”

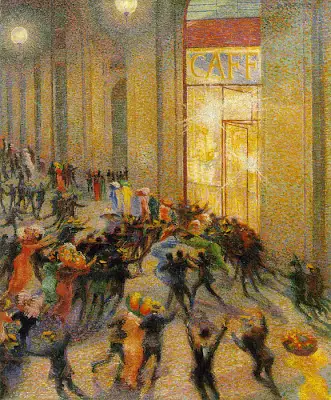

Umberto Boccioni

Umberto Boccioni can be regarded as one of the most influential artists and designers of the Futurism movement. He remained true to the cause until he died in WW1 where he was killed at the age of 33.

Boccioni was a classical artist and graphic designer who at the age of 18 had met with and joined Giacomo Balla in his studies of divisionism and speed.

Boccioni was a pioneer in developing the overall aesthetic as he led the Futurist art direction and produced multiple seminars and manifestos. He was, like other futurist painters, intrigued by the speed and motion of fast cars, airplanes, crowds, and the hustle-and-bustle of everyday life and wanted to depict this motion in his art pieces.

Gino Severini

Gino Severini was an influential Italian painter who made big leaps in Futurist war art. In 1900 he met with Umberto Boccioni and both of them visited Giacomo Balla who taught them the techniques of Divisionism and pointillism. Severini was quick to adopt this style of art in his paintings and even co-signed the Futurist Manifesto (1910) along with the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting in the same year.

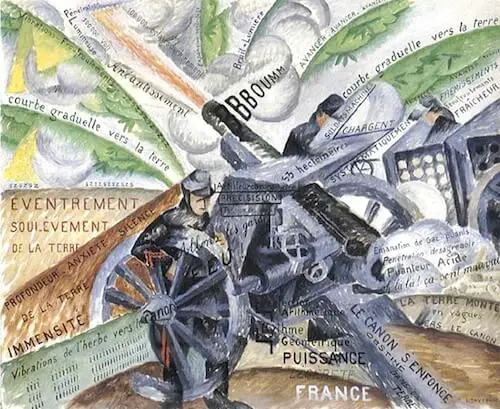

In 1914-15, during the outbreak of the first world war, Marinetti encouraged Severini to produce a series of artworks depicting the war. He did exactly that with his paintings Armored Train and Guns in Action.

He was also one of the people to help in organizing the first Futurist exhibition in 1912 called the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune. In his autobiography, he mentioned that a noteworthy art critic, Guillaume Apollinaire, had mocked the art movement for being ignorant of the main currents of modern art and selfish for its provincialism.

Severini later agreed with Apollinaire and left Futurism to join the Cubism movement in 1916.

Influence & Impact

The Futurism movement was short-lived as it only saw its peak from 1909 to 1914. After the outbreak of the first world war, its first wave came to an end with some of its most prominent members getting killed on the battlefield.

But, Marinetti revived the movement after the war calling it Second Futurism. The phases in the second wave of Futurism could be categorized as Plastic Dynamism, Mechanical Art (1920s), and Aeropainting (1930s). However, Futurism as a movement officially came to an end after the death of its founder in 1944.

It wasn’t for nothing though. Futurism went on to influence many other major art movements including Art Deco, Vorticism, Constructivism, Surrealism, Dada, and Neo-Futurism. Italian Futurism also influenced Russian Futurism in Russia.

You even see Futurism’s concepts of dynamism, speed, youth, and technology in modern culture as well. Movie posters, film effects, music covers, anime, and cartoons all seemed to be inspired by Futurist ideas.

Conclusion

Italian Futurism was a staunch rejection of past cultural heritage, techniques, and traditions. Led by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the Futurist art movement gained quick traction due to its shocking revelations such as the glorification of war and contempt against women.

The movement brought about magnificent pieces of art and rewrote how we imagined everyday life. Due to its emphasis on modernity, speed, youth, and technology, everything from graphic design to fashion to food seemed to have been touched by the hands of the Futurists.

Futurism died out due to the growing condemnation against fascism, which the movement and its followers gladly supported, and officially ended after the death of its founder, F.T. Marinetti.

However, The movement went on to influence future art movements that would morph graphic design into what it is today.

Ironically, despite being known for preaching the “out with the old, in with the new” ideology, the artists would be pleased knowing that future generations took inspiration from Futurism and held on to some of its aesthetic values.

Pingback: URL